[ad_1]

Black holes exert a powerful pull on our imagination, but their weirdness starts way before you cross the event horizon, says astrophysicist Chris Impey

Space

28 May 2020

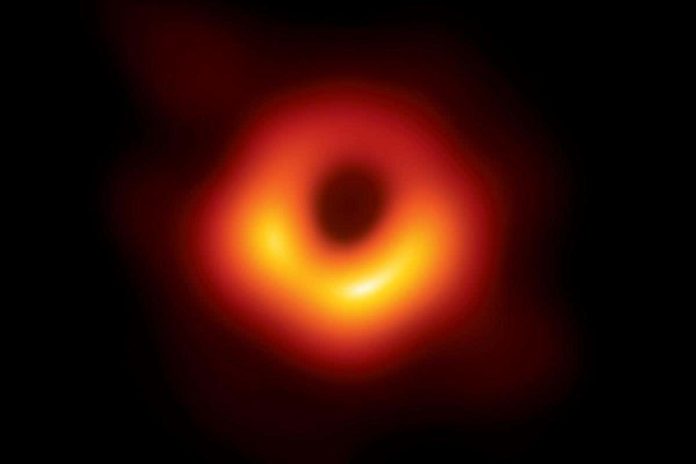

Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration

An English clergyman called John Michell first speculated in the 18th century what would happen if you had a star so massive that its escape velocity exceeded light speed. Back then, however, most people thought of light as waves, and nobody really understood how waves could be trapped by gravity. So the whole idea of dark stars disappeared for about a century – until we entered the world of Albert Einstein.

Einstein was a rock star of physics back in the day. His general theory of relativity is a geometric theory of gravity. It says that mass curves space, or to be more accurate mass-energy (because Einstein had demonstrated these were equivalent with his equation E = mc2), curves a unified space-time, creating what we call gravity.

A black hole is just an object so massive and dense that it curves space-time to the limit. That has truly odd effects. For example, in general relativity, gravity slows time, a fact that’s been confirmed in experiments on Earth. At the boundary of a black hole, called the event horizon, gravity is so strong that time stops completely.

Essentially any object sufficiently compressed can be a black hole. Physics allows for black holes the mass of dead stars, which is to say the size of a small town, but also ones that are much larger and smaller.

In principle, if an evil alien genius empire decided to squash Earth down, it would form a black hole about the size of a …

[ad_2]

Source link