[ad_1]

On February 21, 2020, Italy’s “patient one” tested positive for COVID-19 at a hospital in Codogno, a town in Lombardy – and that was the day the lives of millions of people across the world changed beyond imagination.

The team at the small hospital soon realised this was not an isolated case. The virus had long spread outside the city of Wuhan, China, which had been under a strict lockdown for more than a month.

It took another 20 days for Italy to announce a blanket lockdown, on March 9, closing all commercial activities and confining citizens to their homes.

The lives Europeans had taken for granted in peacetime changed almost overnight: Access to healthcare, free movement and seeing friends and family were no longer a given.

A year later, more than 88,000 people have died after contracting the virus in Italy, the second-highest death toll in Europe after the United Kingdom.

Inequality and poverty are rising as the economy, which had never fully recovered from a 2008 crisis, weakens.

“By the time it came to face the pandemic, the national health system had been severely weakened by a decade of funding cuts,” said Nino Cartabellotta, a leading Italian public health expert, professor and president of Gruppo Italiano per la Medicina Basata sulle Evidenze (GIMBE – Italy’s Group for Evidence-based Medicine).

Between 2010 and 2019, Italy’s public health sector faced cuts and lost revenue amounting to 37 billion euros ($45bn). Doctors of pension age were not replaced, resulting in a shortage of specialists such as anaesthesiologists, and weak local care networks that led to hospitals becoming overwhelmed.

“The virus has always travelled faster than politics and bureaucracy,” Cartabellotta told Al Jazeera.

Al Jazeera spoke to four people whose lives were overturned by the events of the last year:

- Annalisa Malara, the doctor who discovered the first case

- Stefania Principale, a young woman looking for answers to the death of her 41-year-old husband

- Antonella Cicale, an overwhelmed family doctor in Naples

- Lorenzo Stocchi, a healthy young man dealing with the aftermath of the infection

The anaesthesiologist who discovered patient one: ‘It was clear the case was not a common one’

Annalisa Malara, 39, from Codogno, Lombardy

That day, I was on duty in Codogno, a small provincial hospital. I got a call from a colleague in the medical ward saying there was a young patient with very severe pneumonia.

The images I saw showed a very serious interstitial pneumonia, with the aspect typical of viral pneumonia. On top of that, I had seen his chest x-ray from 36 hours earlier. What I was looking at was a very rapid progression. He looked strange, he had bad conjunctivitis and bloodshot eyes, something we later saw in many other patients. He said he had some difficulty breathing, but his condition appeared considerably worse from his exams. He was surprised when I told him he required hospitalisation in the ICU.

It was clear the case was not a common one. When his wife arrived, she told me that two or three weeks earlier her husband had been at a dinner with a colleague that has recently returned from China. Alarm bells began ringing at that point.

But the link was in fact very feeble. That colleague had been in an area 800 kilometres (497 miles) from Wuhan.

At first, we hoped this was an isolated incident, but that night we realised that wasn’t the case. We hospitalised three more patients that weren’t linked to the first. A colleague of mine in intensive care had had a fever for a few days. He came to A&E for the swab and tested positive.

The first weeks were a shock. We were completely overwhelmed by the number of patients that were coming to A&E, with peaks of more than 100 people a day.

The most difficult part was realising the virus could hit anyone – young, old, healthy or ill. Particularly at the beginning, we had to cure those patients without really knowing what this virus was capable of.

We had to close the hospital to family members and sometimes had to announce by phone that their loved ones had passed away. It was very difficult.

Just before we reached the plateau in the first wave, we were in such a state of uncertainty that we thought it was possible we were at the start of a complete catastrophe. Before then, we truly feared the virus could be unstoppable, or at least uncontrollable.

A COVID widow and member of Noi Denunceremo: ‘He video-called us. It was a farewell call’

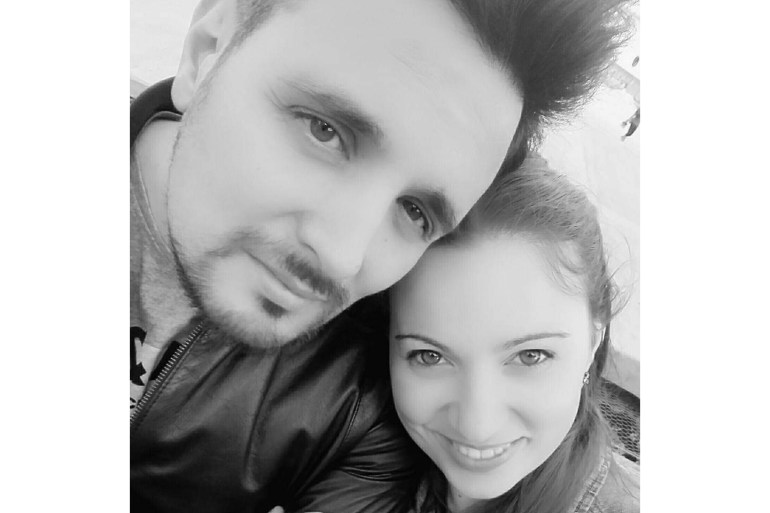

Stefania Principale, 33, from Melegnano, Milan

Principale lost her husband to COVID-19 [Courtesy of Stefania Principale]

Principale lost her husband to COVID-19 [Courtesy of Stefania Principale]

We were living a quiet life with our two children, Andrea and Chiara, who are eight and four.

March 8 came, it was a Sunday. My husband had a fever, we called the family doctor who couldn’t visit him but prescribed some medication. His temperature kept rising and he developed a cough. The doctor said COVID tests could only be done in hospitals. She suggested an x-ray. That showed the start of bilateral pneumonia.

We mobilised, called the helplines to understand what to do – numbers that we weren’t able to reach at first. On Friday, we called the out-of-hours service doctor because symptoms were worsening. They advised us to stay at home, to avoid going to hospitals.

We lived through those days in complete uncertainty, you really didn’t know what to do.

His condition wasn’t good, but they kept telling us to avoid hospitals. We couldn’t tell whether or not that was in our interest. But my husband insisted he wanted to be taken to a hospital. He stayed in A&E for a day and a half, between corridors and makeshift rooms.

He needed respiratory support and was given a CPAP mask. There was no room in ICU. When he received the news a place was available, he video-called us – myself, his sister and his mother. It was a farewell call.

We couldn’t have a funeral for him. I decided I didn’t want to stay in Milan and moved to Perugia, where my brother lives. We thought we could start again from here. The first months were a bit of a bubble. Then I found the group Noi Denunceremo (We Will Report) and I read many stories, all of them like my own. I thought I couldn’t let this go down as something ordinary, because there is nothing ordinary in all of this.

Something I can’t stop thinking about is that when the ambulance arrived at our home, we were in a state of utter confusion. When my husband left, I didn’t say goodbye. I didn’t hug him. I would have liked to tell him don’t worry.

The question is: Who can I blame for all of this?

A family doctor with 1,400 patients: ‘We weren’t provided with PPE’

Antonella Cicale, 40, from Quarto, Naples

Cicale has worked 12-13 hours a day during the pandemic as Italy’s healthcare system strains under the impact of the pandemic [Courtesy of Antonella Cicale]

Cicale has worked 12-13 hours a day during the pandemic as Italy’s healthcare system strains under the impact of the pandemic [Courtesy of Antonella Cicale]

The second wave has been devastating for us. My region and my town, Quarto, were badly hit.

We were more prepared from a medical perspective. I look after patients at home and hospitalise very few cases. If you look out for symptoms and diagnose early, it is very unlikely that patients will need to be hospitalised. And if they are, they have more chances of surviving.

But there were many issues in my area. There were bureaucratic problems with testing, with follow-ups and waiting times for test results.

Family doctors have been largely left on their own. We weren’t provided with PPE, and even though some funding was allocated in an April decree, we only received some supplies in November.

I have 1,400 patients. The worst part was that we had many difficulties handling chronic and oncological patients. Alongside some of my colleagues, I worked 12 to 13 hours a day, but doing anything is difficult at a time of emergency.

I took calls from patients who weren’t my own because there aren’t enough family doctors. The places left vacant by colleagues in pension age for 2020-2021 have not been advertised yet.

Patients without a family doctor who couldn’t go to A&E had nowhere to turn. An emergency in the emergency.

A rehabilitating ICU patient: ‘I still go to the hospital every morning’

Lorenzo Stocchi, 35, from Arezzo province

Stocchi is struggling with long-term COVID-19 symptoms after being infected last year [Courtesy of Lorenzo Stocchi]

Stocchi is struggling with long-term COVID-19 symptoms after being infected last year [Courtesy of Lorenzo Stocchi]

I’ve always been a sporty person. I played league rugby and, last February, I was diving in the Maldives. I’ve never smoked or been seriously ill. I was in perfect health, before COVID-19.

I was mushroom picking with my father, and in the woods I hit the branch of a tree. A splinter got stuck in my cornea. I went to my local A&E but there was no ophthalmologist there so I went to Arezzo, a COVID hospital. Fifteen days later, the symptoms started.

The fever was persisting, so my GP advised me what to do while because I couldn’t get tested for COVID immediately.

Then, in just 12 hours, my condition spiralled out of control. Overnight, I was no longer able to talk as I had to focus on my breathing. I was brought back to the COVID hospital in Arezzo.

I spent the first night in the infectious disease department. After a CT scan, I was made to wear an oxygen helmet. The following day, I entered ICU, where the worst part of all this started.

With the helmet, I couldn’t hear what the doctors were saying. I was so short of breath I couldn’t speak. I was completely isolated. After two days, when the man next to me died, I was destroyed. I felt lonely and desperate, and my family could not fully understand my condition.

I left the hospital on November 12. In the beginning, even the smallest things like taking a shower were difficult because I was breathless.

I still go to the hospital every morning for physical and respiratory rehabilitation.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and brevity.

[ad_2]

Source link